Soviet Stories: Babushka Nina's Wartime Childhood

Three hundred Rubles separated life from death in Soviet Russia

My maternal grandmother’s first memory is escaping Hitler’s March on Russia. Babushka Nina Nesterovna Bondareva was 3 years old. Her parents were lucky to work at a textile factory which got them, Nina, and her grandparents a ticket to join the sixteen million Russians evacuating Moscow in 1941. They were packed into diesel-powered cargo trains, which would stop occasionally for bathroom breaks, fresh air, and let the kids run around. The few people who had money bought food, and they always shared. They cooked in a portable wood stove (буржуйка / “burzhuika” named for the “bourgeois” because it requires so much wood, it’s like the bourgeois who overate — still useful in 2023 for Ukrainians under attack by Russia) that a few people could make a big soup for everyone. They shared to survive.

Nina’s sister didn’t make it. A year old, she got sick on the train and never got better, dying in a dimly lit freight car. Babushka Nina still trembled thinking about her. Nina’s mom was Rh-negative, and her father was Rh-positive, so while the first pregnancy (Nina) went fine, during birth, the Rh-negative mom is exposed to the Rh-positive antigens from the first baby and develops antibodies against Rh-positive, as if it’s a virus or bacteria. For the second pregnancy, the mom’s anti-Rh-positive antibodies pass the placental barrier and attack the fetus’ red blood cells. While the second baby can be born, it dies due to Rhesus disease. Today, this is completely preventable with RhIG shot, costing about $370 on average in the US (if you’re lucky, could be $0 after insurance coverage), a small price to pay for a life.

After several weeks on the train, they traveled 2,012 miles (3,238 kilometers) to Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Her grandparents worked in textile factories to make ends meet. Nina remembers the delicious apricots. Her mother continued to work in the textile factory, while her father became a military driver and was concussed after a bad bombing. He lost his papers and fled to Kamchatka to avoid getting arrested.

After the war, the family (minus Nina’s father) returned to the Moscow region. There, Nina’s mother, Anastasia, faced an impossible choice that cost her life. Born in 1917, she was the same age as the Soviet Union itself. But while the Motherland grew, it created policies that killed mothers: outlawing abortion in 1936, after it was legal from 1920-1936. In her third pregnancy, knowing her child wouldn’t survive due to the Rh factor, she could either carry to term only to watch another child die or risk an illegal abortion and face death herself. Access to birth control would have saved her, but hormonal contraception wasn’t invented until the 1960s, 15 years too late. She got an infection and developed sepsis, normally treatable with penicillin, freely available in other countries. But in the Soviet Union, where corruption contaminated everyday life, the doctor demanded a 300 Ruble bribe by tomorrow to treat her.

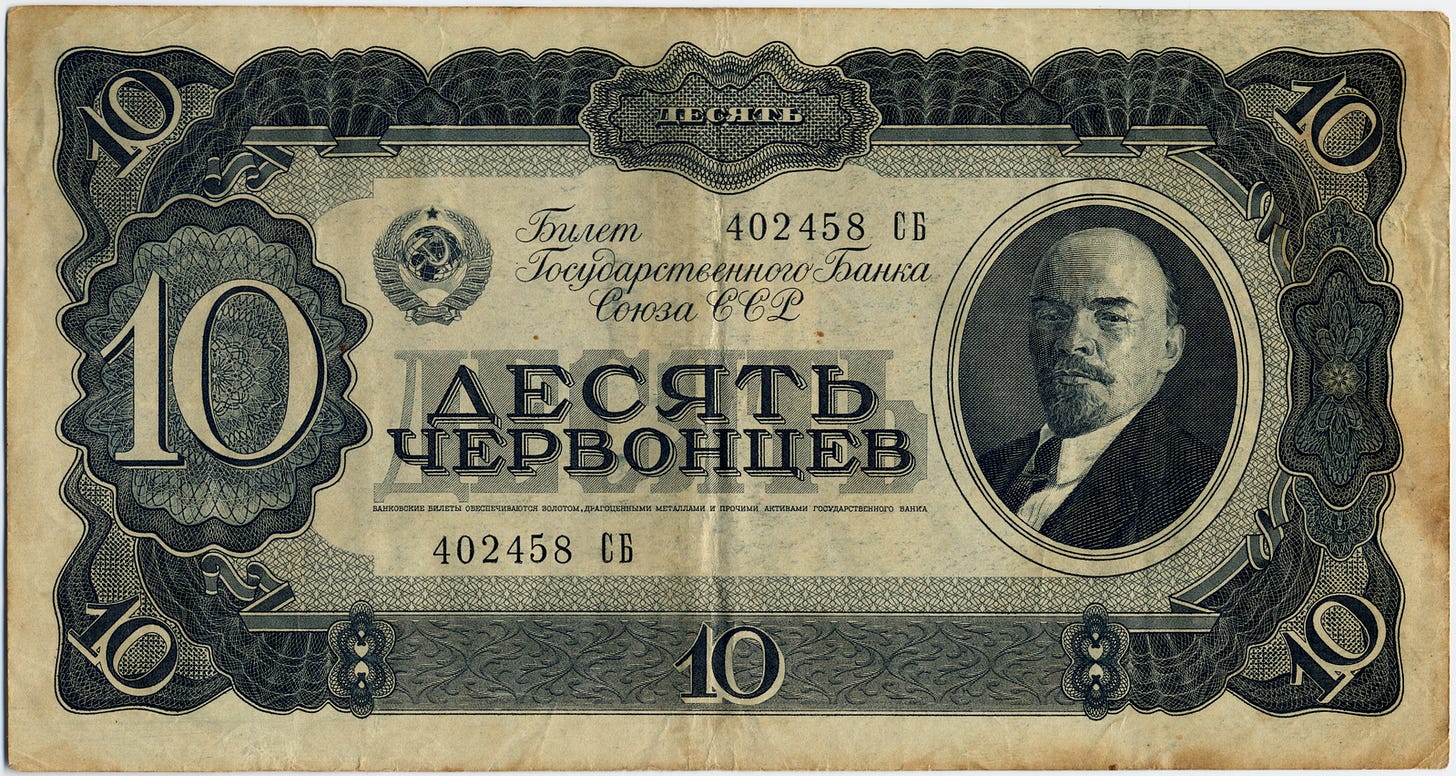

Her grandparents scrambled to save their daughter. Her grandfather, a skilled repairman, took the express train to a neighboring district to work day and night at another factory. He earned the 300 Rubles, but came back a day too late. His daughter had already died. Angered beyond recognition, his toughened hands slammed the banknotes onto the floor where they lay worthless. A year of rent in Lenin’s useless faces littered the floor, staring back at eight-year-old Nina sitting in the corner, searing an image in her memory for the next eight decades. The image of money that could have saved her mother yesterday, but couldn’t bring her back today.

Nina worked as a radio engineer on satellites to send rockets into space in the secret town of Zheleznogorsk, Siberia for her adult life. In the 2010s, she took a computer class to learn to use a laptop and Skype to call her relatives in the US. At the beginning of her computer classes, she’d say to the computer mouse, “You and I are going to be friends today.” Thanks to her efforts, we talked regularly on Skype since 2012, until her passing in 2024.

Her stories live in my bones and flow in my veins to you, a reminder that the challenges of starting Seanome pale in comparison to the hardships she endured in her first decade of life. Watching her infant sister die on a refugee train, losing her mother to the failed Soviet system, and seeing her grandfather’s anguish over meaningless money, these moments shaped her life and echo through mine. I’m grateful to learn from Babushka Nina’s strength, so I can appreciate the privilege of building Seanome today.